Elementary – The Naming of Steels Constituent Elements

Never let it be said that we at West Yorkshire Steel never think about anything but metallurgy. Having eventually caved in to the constant ‘but you must watch Breaking Bad’ calls, we settled down to watch an episode or two with a bowl of popcorn.

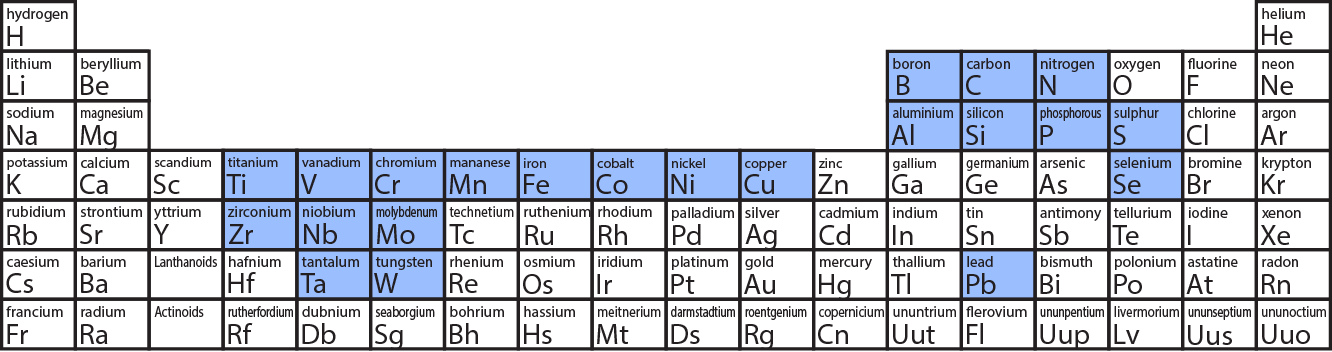

It was very interesting from the very start, even the titles for the show set us thinking. The design of the show includes names of cast and crew members shown in the style of elements on the periodic table, so ‘Kris’ would be shown as ‘Kris’ referring to the chemical symbol for Krypton.

It peaked our interest in how elements get their names, and specifically how the constituent elements of steel got their names. We did a little looking and found that there are some interesting etymological turns…

Carbon, the content of which has a profound effect on the steel, is actually from the French ‘charbon’ which literally means charcoal. The original word still exists in common usage, when we refer to the carbonisation and blackening on the bottom of pans and barbecues. It was discovered and named by Antoine Lavoisier in 1772 and has remained unchanged since.

Silicon came along around fifty years later and was discovered by Swedish scientist Jakub Berzelius. In Swedish it’s known as Silicium, which started as ‘silica’ from the original Latin name for flint, a hard stone made from silicon dioxide. Silicium was so called due to the custom of naming newly discovered elements ‘-ium’, but the English was changed to end in ‘-on’ due to its similarity to carbon. There are also other names of silicon dioxide, the most widely known of which is quartz, famous for its use in watches.

The discoverer of Manganese, Johann Gahn took a slightly more pragmatic approach to the name, opting for something descriptive. His original experiment took pyrolusite (MnO2) and reduced it to carbon dioxide (CO2) and manganese (Mn). As pyrolusite has magnetic properties, he decided to go with the Latin word for magnet, ‘mangnes’ and the name stuck.

One of the oldest elements in steel is Sulphur. It’s so old that it appears in the book of Genesis in the Bible where it is known as ‘brimstone’. Unsurprisingly for something so old, the name also derives from Latin as ‘sulphurium’ which became shortened to sulphur. In recent years this has been officially changed to Sulfur, but nobody is sure quite when or how this actually occurred.

The oldest element in steel that wasn’t known in ancient times is Phosphorus and it happens to be the most poetically named of the constituent elements. Literally meaning ‘bringer of light’ (‘phos’ – light and ‘phoros’ – bearer, carrier or bringer), its name derives from Greek and is believed to have been found by German alchemist Henning Brand in 1669 as the 13th known element. As a highly reactive metal, it was known as the Devil’s element and was subsequently used for explosives, nerve agents and poisons.

The Devil also appears to raise his head as Old Nick again in another steel ingredient, Nickel. Thought to be from the mineral named ‘niccolite’ which is in German ‘kupfernickel’ or Old Nick’s Copper. It was discovered by Alex von Cronstedt and demand for nickel rocketed following its use in steel.

Chromium is so called because of the many colours of its compounds, as ‘chroma’ in Greek literally means colour. Nicolas-Louis Vauquelin found Chromium in 1797 and the name is literally just a nod to the way that scientists would commonly come across the element.

Lastly Molybdenum came around 1778 and is the last of the steel ingredients to look to Greece for inspiration. Literally meaning ‘like Lead’ it was named by Carl Wilhelm Scheele who more than likely took a descriptive name in Greek due to Lead’s chemical shorthand of Pb coming from Plumbum which is a Latin word. Using Greek to describe one element in reference to another which takes its name from Latin may well have been apparent to the scientists of the day; a clever hat-tip from the new to the old and a very simple way of avoid confusion between the two.

Having run out of elements present in steel, it closes an interesting detour through the system of cataloguing chemicals and ends a pleasant evening’s reading about the history of steel. However, we’re now out of popcorn, we’ve still not seen Breaking Bad and we can no longer claim that steel isn’t all we think about!

Take a look at our elements in steel page for more information to learn more about how they affect the properties of steel.

When I worked in the ’50s at Low Moor Alloy Steel we made steels with all these plus vanadium, tungsten and niobium/columbium . Just once we made a special order containing Boron: when the 5 ton melt was ready to pour the furnace first-hand came up to the lab and asked us to weigh out ‘an ounce of boron’. we duly weighed from his bag 28gms of the metal which he took and stirred into the molten steel. One part in 200,000! I often wondered how well it was distributed through the melt.