Unexpected Side Effects in Steel

It’s no secret that we at West Yorkshire Steel love a good story and a bit of crime drama always goes down particularly well. One recent series threw up a neat little quandary – how to fake something that can’t possibly be recreated. Our detective is trying to prove that an extremely rare bottle of wine owned by Benjamin Franklin is a fake; it is, in fact, a modern wine simply put into an age-appropriate bottle, using cork and wax from the right time period.

The killer blow comes because the wine can be radioactively tested for Caesium 137 – a radioactive isotope that doesn’t exist in nature. During the 1940s, the testing of atomic weapons not only created the isotope, but distributed traces of it all over the world. Any wine racked into bottles after 1945 would have tiny, but measurable amounts of Caesium 137, but the Ben Franklin wine would not… and cue the race to try and prove the authenticity!

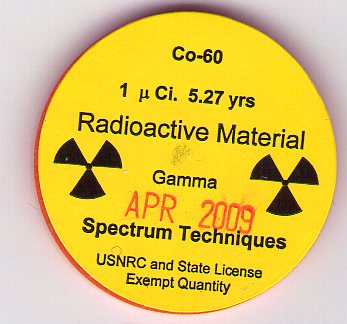

This all seems quite familiar to anybody working in the steel industry, as Caesium isn’t the only element to have a radioactive isotope created by nuclear reactions; Cobalt 60 is also created in a similar manner. Cobalt 60 is classed as synthetic, as the conditions needed for this particular variation of the element to form are entirely man-made and only exist in a nuclear reactor.

Cobalt is a component of steel, needed to give the metal a range of characteristics. Steel produced since 1945, however, is now at risk of exhibiting radioactive properties, thought to be the result of uncontrolled disposal of Cobalt 60 into scrap metal processes. There have been some instances of steels that have contained too much of the isotope and therefore have shown up to be radioactive. Although Cobalt is needed in varying amounts dependent on the type of steel you’re creating, Cobalt 60 is classed as a contaminant.

The interesting thing is that this has created a valuable market for iron and steel produced before the 1940s. As we know, steel is one of the few materials that is 100% recyclable; the steel it produces is as good as the one that came before and there’s not really a limit on what can be done when recycling steel. Steel produced prior to the proliferation of nuclear processes is known to be free of Cobalt 60, therefore can be reworked and re-forged without issue, meaning it’s more in demand.

Cobalt 60 isn’t actually ‘the bad guy’ as it can serve some extremely useful purposes; everything from food and blood irradiation, sterilisation, radiography and radiotherapy treatments for cancer. The main problem is that if the concentration of this particular isotope becomes too great, there are concerns about prolonged contact or exposure to the low levels of radiation.

Seeing how advances in our technology, understanding and processes change things forever, in ways that we don’t expect can be absolutely fascinating – whether it’s the steel used in a grand, expansive suspension bridge or a small bottle of wine!

Photo credit: Wikipedia